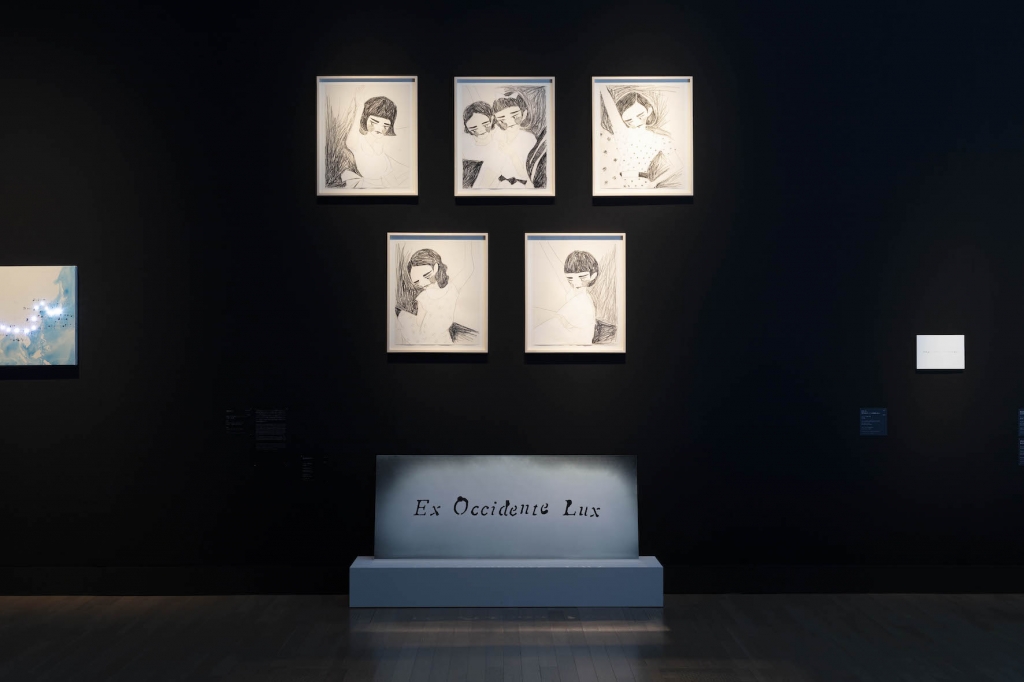

”She Waited” Erika Kobayashi

“Image Narratives: Literature in Japanese Contemporary Art”

Location: The National Art Center, Tokyo

Period: August 28 – November 11, 2019

1936

There, in the little town where the narrow Silberstraße ran

straight through, starting at the church on the hill,

she looked up.

A ladder leaned against the stone wall beneath the red domed roof of a building

where the Olympic emblem was being carved into the stone:

five rings and the word OLYMPIA, and between them the date:

1936.

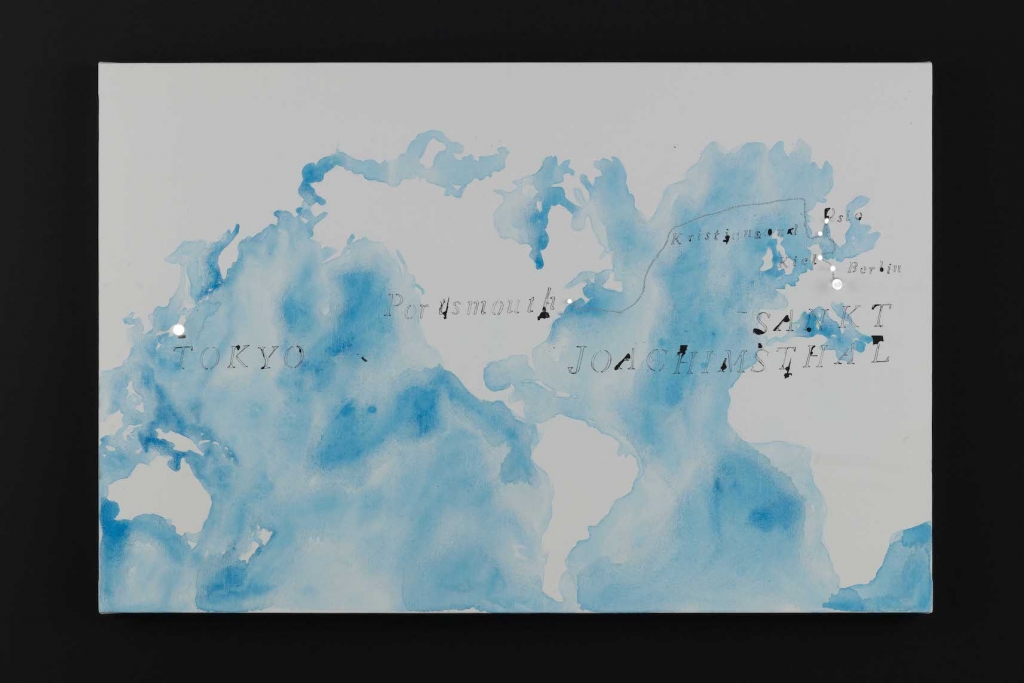

This was Czechoslovakia, formerly Bohemia,

a place called Sankt Joachimsthal—Saint Joachim’s Valley.

She waited—

for the Olympics

for the sacred fire to come to her little town,

for the fire, for its light, to illuminate her little town.

There’s a reason this narrow road is called the Silberstraße.

In the 16th Century, in Saint Joachim’s Valley, silver first emerged—

over 5000 men arrived, ready to get rich quick—

from Saxony, in Germany—

they came and dug deep into the earth.

The silver was minted into coins that spread all across Bohemia,

coins called Joachimsthalers, or thalers for short.

They eventually reached even the New World, as dollars—

for this is the origin of the dollar.

Torch in hand, men descended into darkness,

excavating deep into the earth,

but as they dug, less and less silver emerged

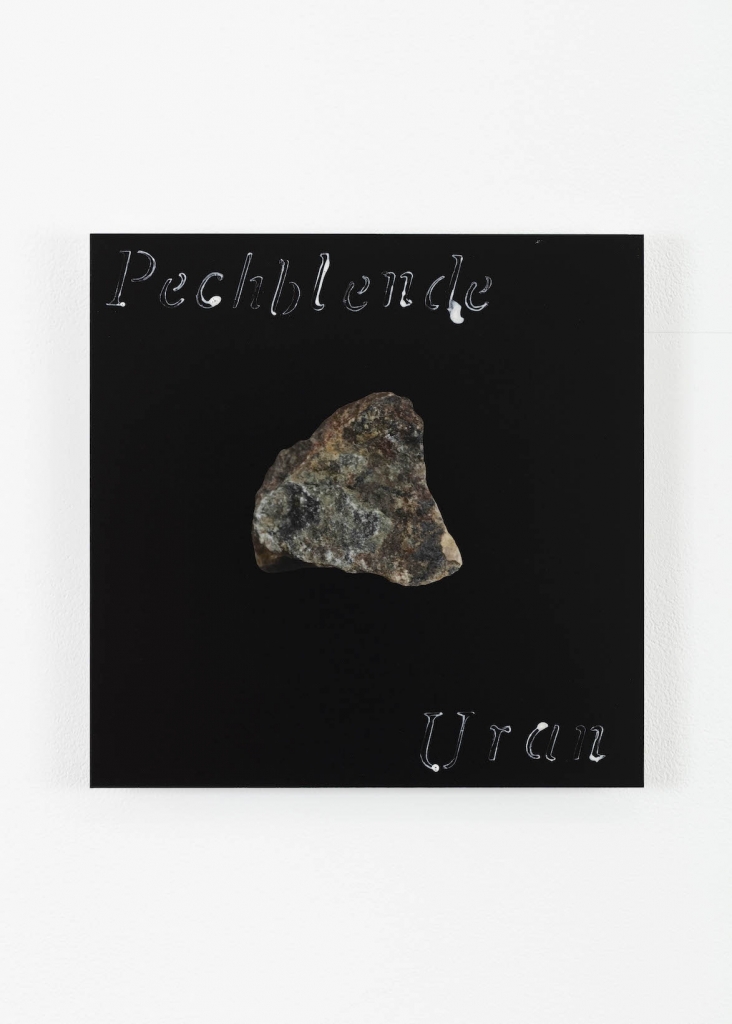

replaced by more and more mysterious shiny black stone.

Among the men, a mysterious disease began to spread—

their bodies grew sluggish and would bleed without stopping—

and so they began to call the shiny black stone pitchblende,

German for accursed stone.

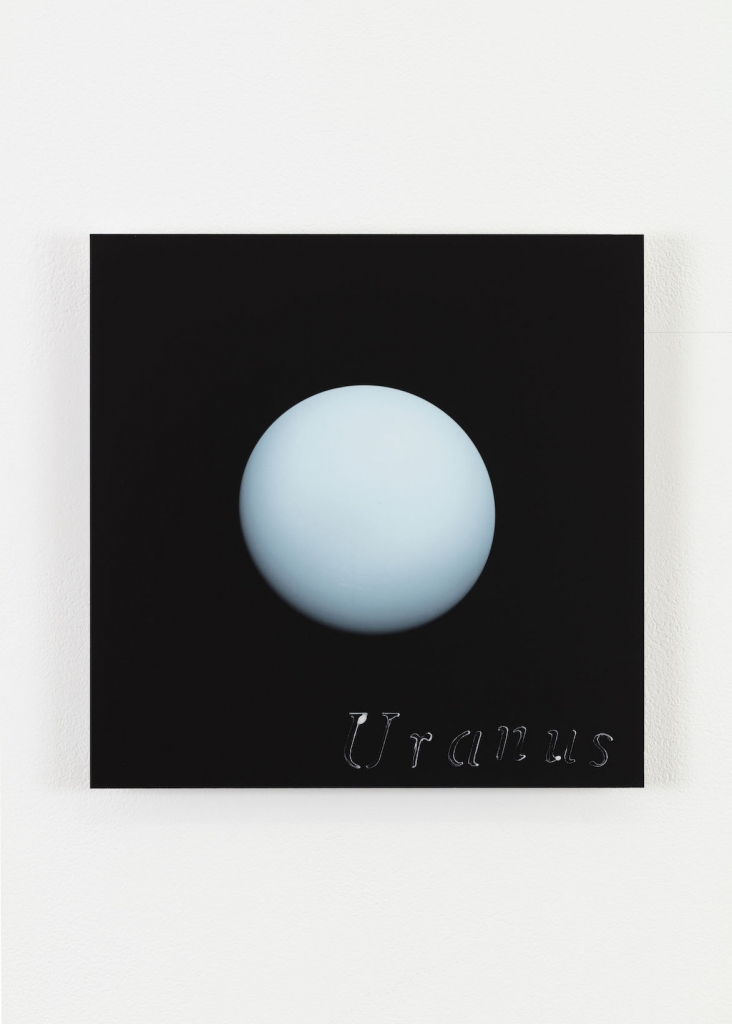

In the 18th Century, a new element was discovered within this accursed stone.

It was given the name uranium, after the planet Uranus.

When uranium is mixed with glass, it glows fluorescent green under ultraviolet light.

Soon uranium glass spread all throughout Europe.

It was prized by the aristocracy, made into wine glasses, vases, necklaces,

even instruments for irrigating the eye.

According to Greek myth, Uranus, the sky god,

was born to the earth goddess Gaia despite her virginity,

and when mother and son made love,

the world was visited by darkness.

At the same time she was looking up at the Olympic emblem being carved into the wall,

eleven virgins had gathered

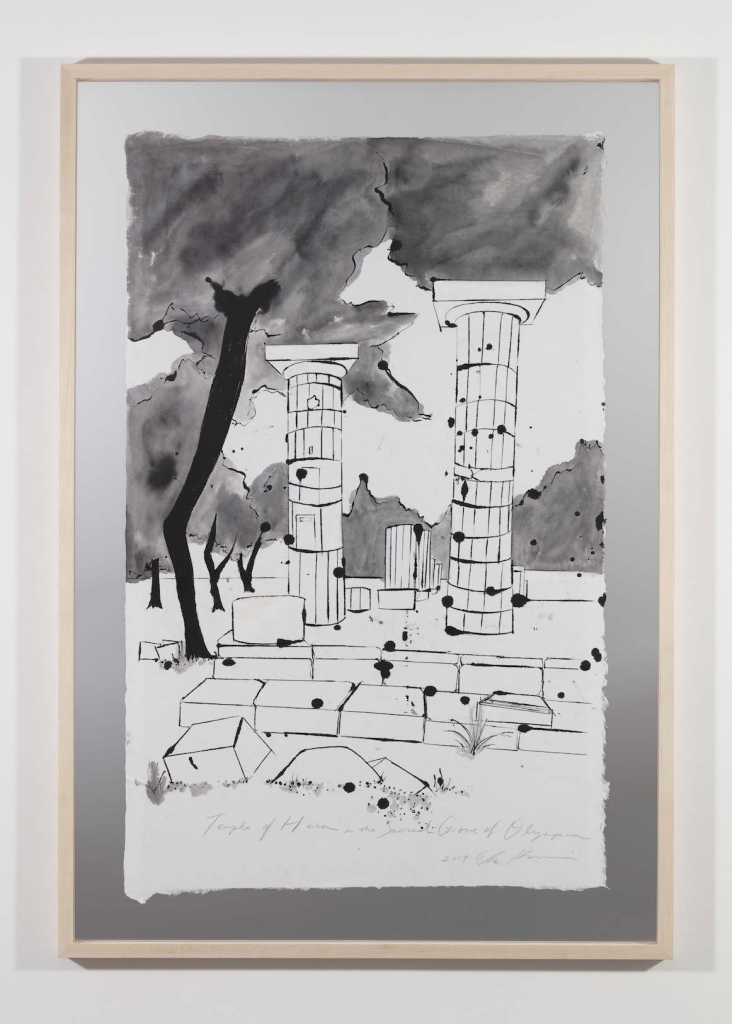

in Greece, at the ruins of the Temple of Olympia,

all dressed in white.

During the ceremony, the virgins gathered the light of the sun using mirrors.

It was July 20th, the first time the sacred fire relay took place.

The flame was resurrected, the sacred fire passed from torch to torch—

the fire stolen from the sun and given to humanity by Prometheus—

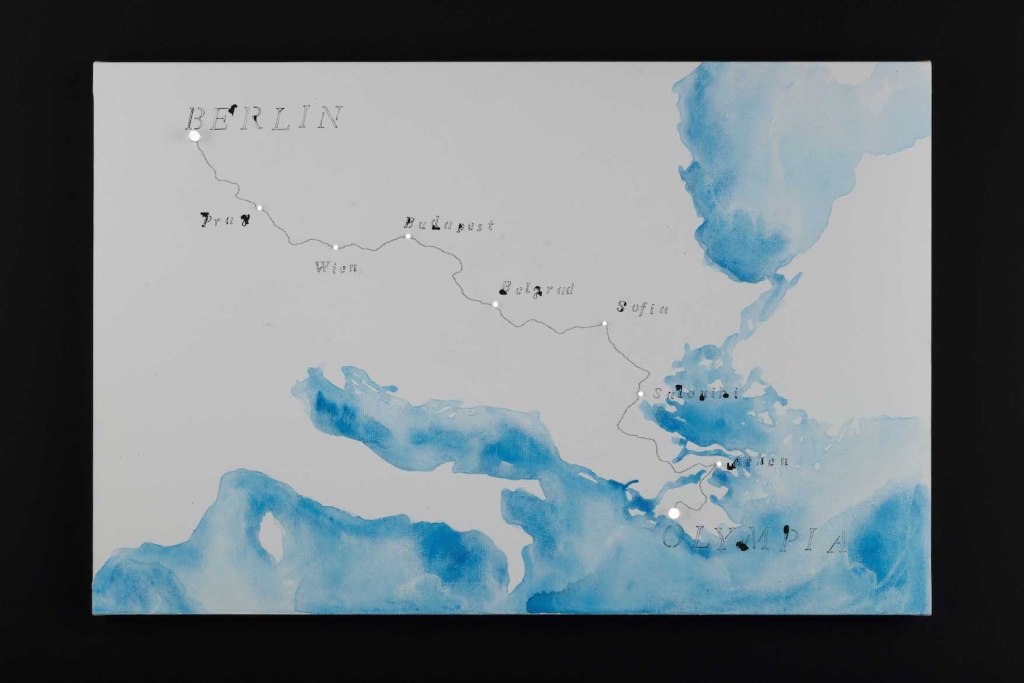

from Greece, the Land of Olympia, to Berlin, in Nazi Germany—

to the Olympic Stadium, where the Opening Ceremony took place, led by Adolf Hitler.

It took twelve days to make the journey.

3308 runners carried the torch,

the flame passing hand to hand, bringing its light.

And she waited—

for the sacred fire to come to her little town,

for the fire, for its light, to illuminate her little town.

Finally, at one in the morning on July 31st, the sacred fire reached Prague,

and then at 4:30am reached Straskov, then Terezín at 6:15, then Teplice at 9—

but the sacred fire never reached the little town.

1938

It was two years after the Berlin Olympics.

The Nazi army invaded the area as if following the sacred fire’s path,

their tanks made by Krupp, the same company that manufactured the torch itself—

the flames burned all in their path to ashes.

The Nazi army arrived in the little town the sacred fire never reached.

Torch in hand, men descended into darkness

excavating deep into the earth,

but instead of miners, now it was prisoners of war brought by the Nazis who mined the accursed stone.

In the center of a big city filled with brand new buildings

thrown up under the banner of reconstruction following an earthquake’s devastation,

she looked up.

Flags with red suns in their center joined flags bearing the Olympic emblem,

flying as far as the eye could see.

On the posters showing Mount Fuji and the Olympic rings in gold,

letters spelling TOKYO were set beside numbers spelling out the year:

1940.

It was the 2600th Anniversary of the Founding of Japan,

and this was Tokyo, the Imperial Capital of the Empire of Japan.

She waited—

for the Olympics

for the sacred fire to come to her city,

for the fire, for its light, to illuminate everything around her.

1940

It was four years after the Berlin Olympics.

The fire of Olympia, Prometheus’ gift, was to be borne from Greece this time to the Far East,

to the stadium where the Opening Ceremony would occur in Tokyo,

the capital of the Japanese Empire.

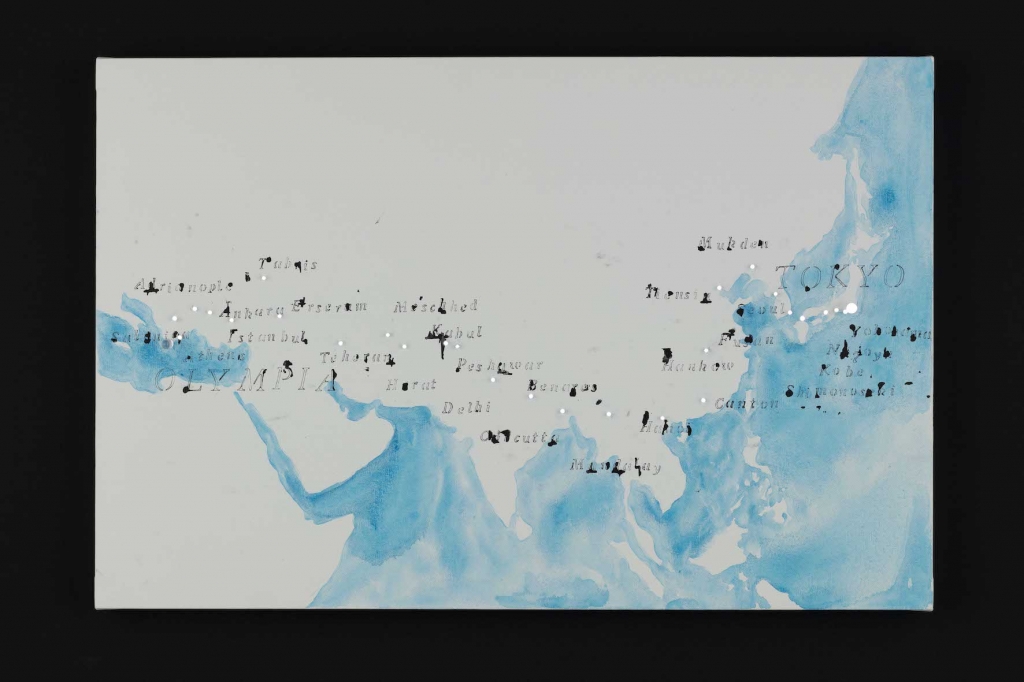

It was to be a grand Olympic relay to bring the sacred fire from

Olympia to Athens, then Istanbul, Ankara, Tehran, Kabul, Peshawar, Delhi, Kolkata, Hanoi,

Guangdong, Tianjin, Seoul, Busan….

The flame was to be borne by men on foot and horseback,

its light crossing Eurasia eastward hand to hand until it reached the Land of the Rising Sun.

Would the Latin phrase ex oriente lux end up being changed to ex occidente lux?

She looked up at the flags with suns in their centers,

but they were no longer accompanied by those with the Olympic emblem.

All that passed by her were parade floats for the 2600th Anniversary of the Founding of Japan.

It was November 10th.

The streets were dim, the lights shut off by government decree to conserve power.

She waited—

for the Olympics

for the sacred fire to come to her city,

for the fire, for its light, to illuminate everything around her.

But the Olympics were never held,

all the men were sent to the battlefield,

and the sacred fire never reached her.

1941

It was one year after the Tokyo Olympics failed to happen.

The Japanese Imperial Army not only retraced the path of the torch relay that was never run,

but went east as well,

borne by bombers rather than horses, flames burning all in their path to ashes,

attacking America, bombing Pearl Harbor in Hawaii:

the Second World War had begun.

Torch in hand, men descended into darkness

excavating deep into the earth.

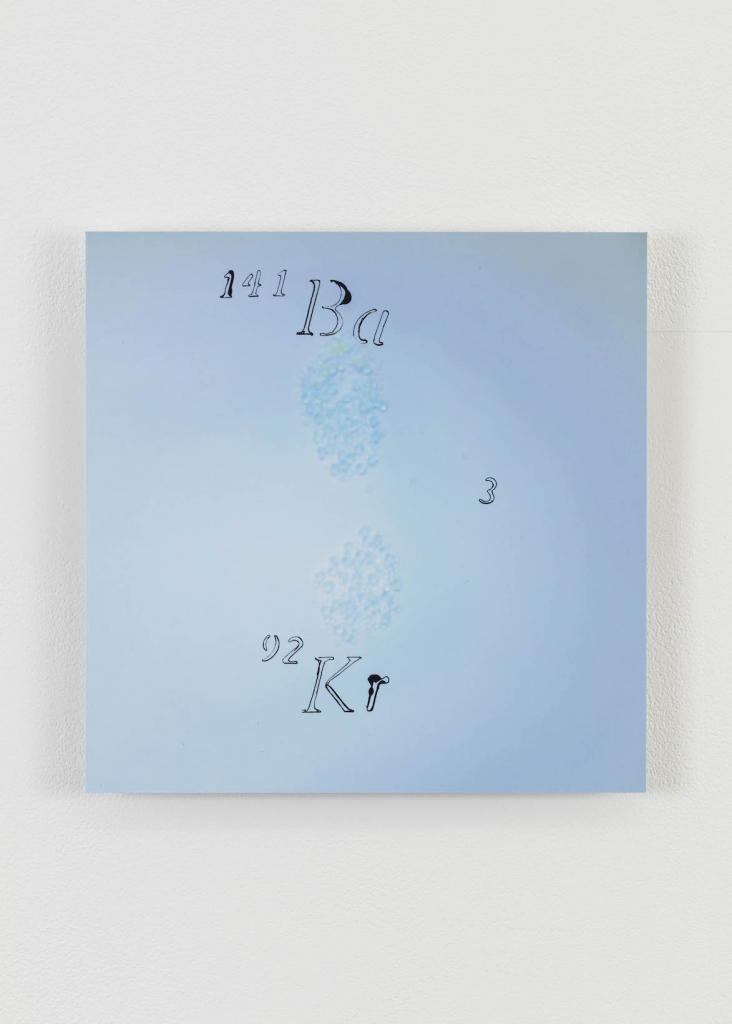

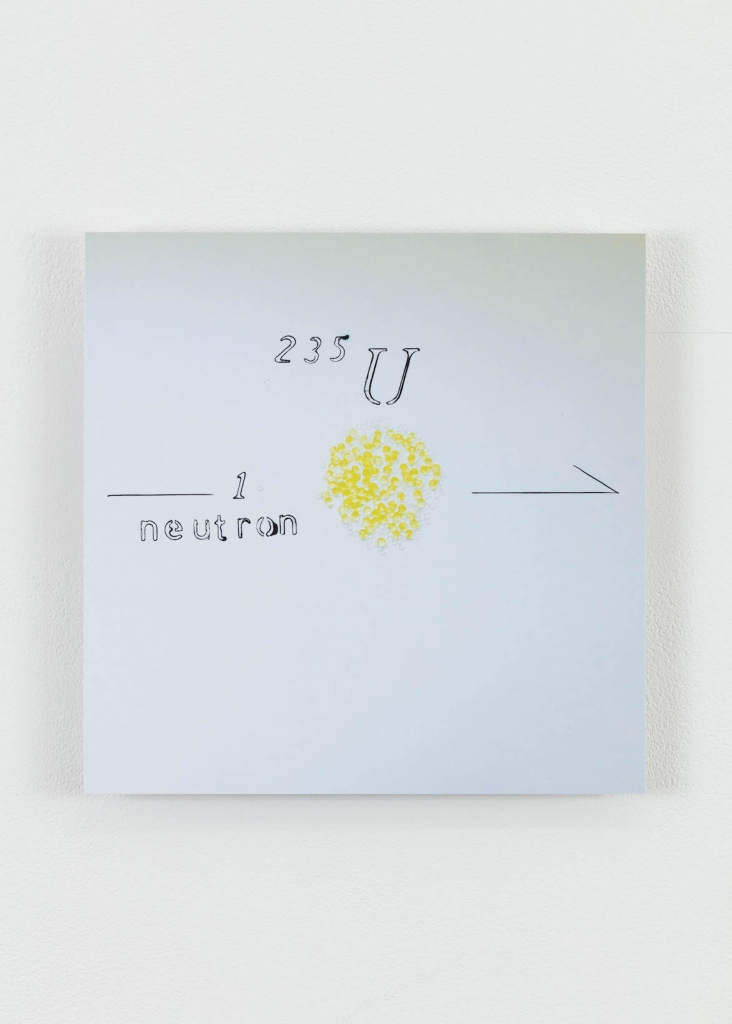

The nuclei of uranium atoms could now be split,

and the energy produced could create the greatest bombs the world had ever seen—

bombs that we now call nuclear weapons:

10 kilograms of uranium 235 were needed to make one.

A top secret nuclear weapon development plan called the Ni-Go Research Project was begun,

a collaboration between physicists at the National Institute of Physical and Chemical Research and the Japanese Imperial Army.

A plan was hatched to transport large amounts of uranium

from Nazi Germany to its ally, the Japanese Empire.

Accursed stone was transported by rail from Saint Joachim’s Valley to the outskirts of Berlin,

where uranium was extracted from it and taken to Kiel Bay—

passed hand to hand, it was placed in a submarine to be transported along the Atlantic Ocean floor,

bound for the Land of the Rising Sun.

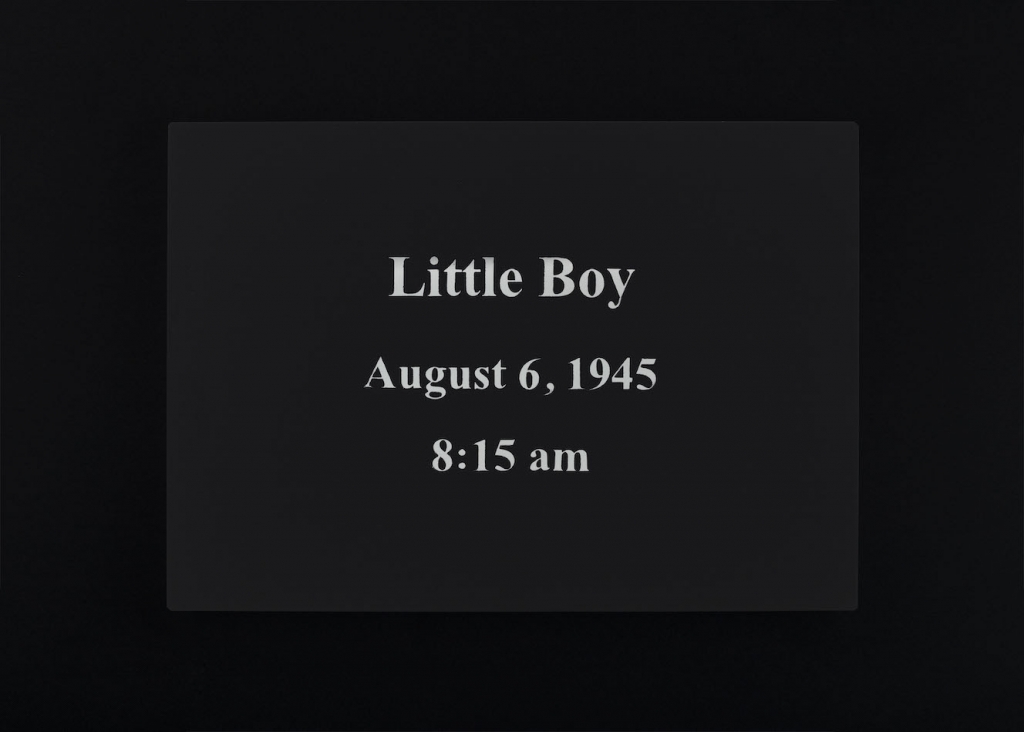

1945

Kiel Bay, where the yacht races of the Berlin Olympics had been held,

back when the sacred fire illuminated the nation,

was once more illuminated by flames.

The naval base, the town hall, the church of Saint Nikolai, the opera house—all were on fire.

The submarines known as U-boats were anchored in the Bay. They were called Grey Wolves.

One bore 47 brown packages of uranium.

The U-boat’s number was only one off from that of the uranium within it: U-234.

Two men from the Empire of Japan accompanied the men from Nazi Germany on the U-boat

to take the uranium east.

She waited.

In the streets of Tokyo, where the Olympics had failed to come,

where the sacred fire had failed to reach,

she looked up at the dark sky.

Rumors repeated:

the scientists of this great country were making a bomb more powerful than any ever seen before,

a bomb called a uranium bomb—

a matchbox-sized piece would be enough to bathe the streets of New York in flames.

Torch in hand, men descended into darkness.

Bearing its uranium cargo, the U-boat crossed the ocean floor.

As it headed south across the Atlantic, a coded message was received:

Nazi Germany had unconditionally surrendered.

But even if Germany had fallen, the Empire of Japan had not!

The two Japanese men onboard the submarine insisted in fluent German—

If this uranium is delivered, the bomb can be created—

it can be created and used and the war can still be won!

The target would be Saipan—

if Saipan were taken out, the distance would be too great for the Allied planes

and land war would be avoided!

But it was decided to surrender the submarine to the Americans

and the two Japanese men swallowed Luminal,

collapsing into a heap on a bed, snoring unnaturally,

the white bedsheets soaked in black diesel.

The black flags announcing defeat were hung from the periscope once the U-boat had surfaced

while the bodies of the Japanese men sank to the floor of night-dark sea.

She waited.

The Tokyo streets were now illuminated, bathed in flames.

The air raids of the land war had begun.

And she waited—

but the uranium failed to reach her,

and the bomb was never completed.

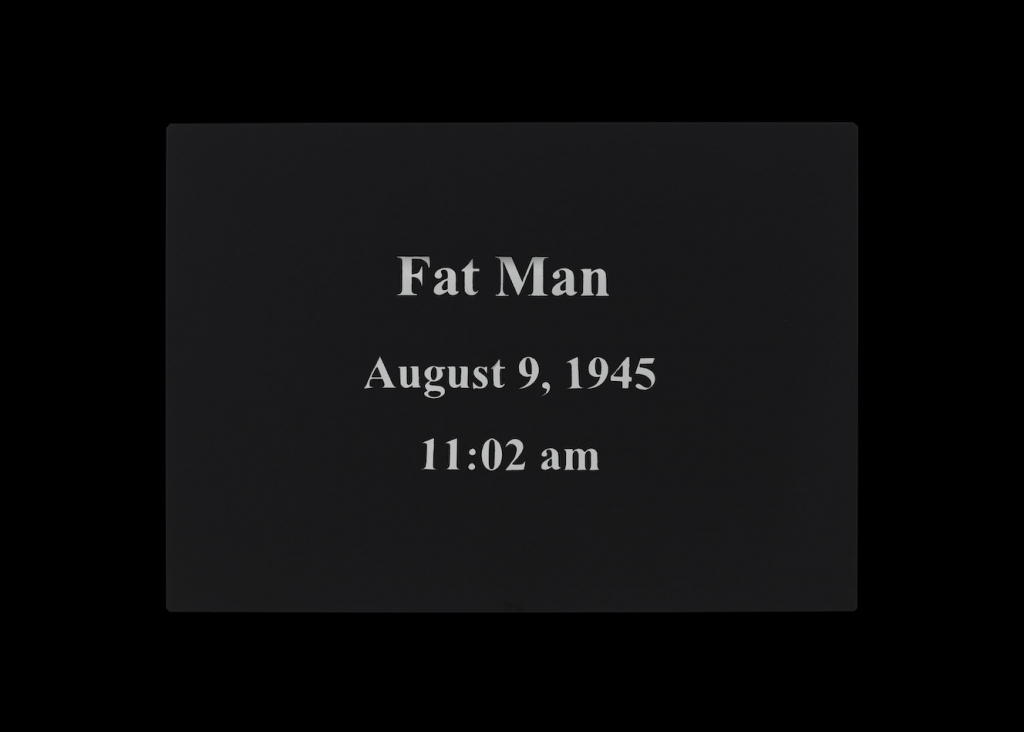

The bomb she’d so anticipated ended up dropped on Japan instead—

bombs named Little Boy and Fat Man,

illuminating everything around them as they burned everyone to ashes.

The war ended,

but her life, their lives, did not.

Torch in hand, men descended into darkness.

Translated by Brian Bergstrom

©️Erika Kobayashi, “Image Narratives: Literature in Japanese Contemporary Art”, 2019, The National Art Center, Tokyo, Installation View, Photo: Shu Nakagawa